Bumpy Road

Pregnancy changes everything

by Rebecca Barry | March 1, 2009

One day you wake up stupid and sick. You can't remember what you were saying in your last sentence. You pour hot water through the tea strainer and down the drain without putting a cup underneath it. You want to throw up all day, but you also want to eat Campbell's chicken and dumpling soup. Vegetables make you sick. Milk makes you sick. Your husband sleeping too close to you makes you sick. "Congratulations," says your doctor. "You're six weeks pregnant." You have a thesis to finish and two classes to teach. You turn to your husband and say, "You've ruined my life."

You always thought you'd love being pregnant — that your body would take to it happily, the way it did to bourbon. But you only feel good when you are eating, which then makes you sick. "It will pass," says your mother, your doctor, your friends. "It probably won't," says your mother-in-law. "I had my head in the toilet the whole nine months when I was pregnant. Didn't I, Tony? I only gained nine pounds, and six of them were the baby." You have already gained ten pounds. You wonder if you should go on a diet. Instead, you eat an entire pizza.

You get stupider. You can't remember your students' names, and one day you can't think of the word "voyeuristic." You stand in front of 22 young writers trying to act it out. "The desire to look into other people's lives," you say. "You know, what we all like to do as writers. What's the word I'm looking for?"

"Sad?" says a student, who will later turn in a journal with an entry that starts, "Today was my first day of writing class. The professor's boots scared me." You consider giving that student an F.

"You lose 40 IQ points when you get pregnant," says your friend Sheila, who sometimes sees ghosts. She's been calling you weekly to ask how you are, even though she gave up a baby a year before she got married. She and the baby's father, who is now her husband, weren't ready. They didn't have the money. They weren't married. She took some abortion pills, and after they slid down her throat she cried for two hours. Now sometimes, when she passes a mirror, she sees a small shadow hovering near her head.

By your third month, according to the updates from your baby guide, which e-mails you every week, your baby's eyes are finally on the front of its face and its ears are in the right place. It still has gills and is smaller than an avocado. You, however, are huge. "You might be beginning to show," baby guides say. You've been showing for a month. You get mad at baby guides. Also Gwyneth Paltrow, who has the same due date as you and looks like a reed. You resent all the movie stars who are getting pregnant like they're buying a new pair of shoes. Now you can't even do this without the pressure to look like them. You are still nauseated and very pale. You tell your thesis adviser you're pregnant. "Hooray!" she says. "Have you thought of a name yet? Bucephalus is widely underused."

You want to like being pregnant more, especially since everyone is happy for you. But you feel like you have too quickly become a vessel for everyone else's happiness: your husband's, your mother's, your mother-in-law's. Jerry Fallwell's. Your brother who loves golf sends you a card that says, "Congratulations! What a magical year you have ahead!" and this makes you feel like everything else you've done in your life doesn't matter now that you're going to be a mother. "It's not magical," you say. "It's biological. A monkey can do it." You are already tired of babies. Babies, babies, babies! The polar ice cap is melting and songbirds are dying. "Do you know what human beings do?" you say to your husband. "They kill everything. What would be magical is if I gave birth to a penguin. They're endangered." Luckily, according to baby guides, Bucephalus, who has just lost his or her tail, can't hear yet. Your husband tells you not to worry, you will probably give birth to a liberal, and they will soon be endangered too.

You notice that every time you say you don't feel good in your pregnant body, people say, "You're not fat, you're pregnant," as if being pregnant should solve everything. But you loved your pre-pregnant body, and this new one has changed into a factory that has nothing to do with you. Your legs have thickened, you've begun to blush easily, and your breasts are so busy you wouldn't be surprised if they got up in the middle of the night and set up a cafeteria. It amazes you that no one talks about this, that the only rhetoric you hear is that pregnancy is beautiful. When you say you feel huge, people tell you you're gorgeous. Glowing. Beautiful. But to you, it's not beautiful. It's powerful. You have double the normal amount of blood coursing through your veins. Two hearts beat inside you. You have never felt more ferocious. When your Pilates teacher tells you not to walk alone at night, you tell her not to worry: You could walk into a war zone and say, Bring it on. Point a gun at me. I will break you with my bare hands, because I am pregnant, and you couldn't handle the nausea alone.

You're pretty sure you used to be more conciliatory.

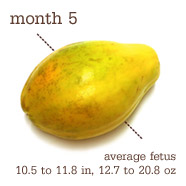

By the fifth month, baby guides tell you that the baby has begun to drink its amniotic fluid. You assume this means that not only is it swimming around in its own toilet, it's now drinking the water. "Which means it has a dirty mouth," your husband says. "Just like its mother." Then he falls asleep.

You stay up late reading about birth defects and the vitamins you should be taking. You are still nauseated. You look at your husband, who is sound asleep. You think about how all he had to do was have sex with you, and how you have to deal with everything — how much this is going to hurt, the breast pump, the sagging boobs when you're done nursing. You think about how much money you've spent in your life on tampons, birth control, ibuprofen, bikini waxes — about $32,560. You think about what men get away with in the world and you can't believe they have so much political, social and economic power.

You miss getting drunk.

One day, the baby stops kicking you. For 14 hours you feel nothing — no nausea, no fluttering, no slow, rolling motion in the pit of your abdomen. You are lost and unmoored, the way you felt when you put your parents on the train to the airport after they visited you in France, and their sweet, familiar faces got smaller and smaller until they were gone. But then there is movement again. A blip, a ripple. Unbelievably relieved, you tell your mother-in-law, who is visiting. "That's the thing about birth," she says. "You're that much closer to death."

Then she tells you a story about the time she saw the husband of a woman who had cut a pregnant woman's stomach open and took her baby.

Instinctively, you put your hands on your belly to cover Bucephalus's little ears, which now work, according to baby guides.

"That's a terrible story," you say. "That's the worst thing I've ever heard."

"I know!" says your mother-in-law happily. "She met her at Wal-Mart."

You worry that you aren't connecting to the baby. You worry that you aren't connecting to anyone else because you keep saying what you think. "I hate being pregnant," you say to a group of people you barely know (and then the whole way home you apologize to the baby: "It's not you I hate, Bucephalus, it's the pregnancy"). When one of your colleagues says the main character in a story is pathetic because she's promiscuous, you put your head in your hands and say, "Your argument is hurting my brain." No, you tell your students, who want to know if they can e-mail you another draft of their essay, if they can make an appointment outside of your office hours, if they can make up the four classes they missed because they work in a nightclub and don't get out of bed before three in the afternoon. "That's bullshit," you say, when one of them cites a study about women abusing men more than men abuse women. You haul your pregnant self out of your chair and say, "Show me that shit-for-brains study." (Miraculously, your evaluations that quarter are the best they've ever been.) "Yes," you say when people offer you a bite of whatever they're eating. Then you take three times more than they offered you. "Go bother the dog," you say when a friend asks you how you can be pro-choice when you're growing a baby yourself, when you can't even kill a lobster and looking at a tank of them waiting to die makes you impossibly, inconsolably sad.

Then one day you're sitting alone on your porch with your baby inside you and you look up at the birch tree in your front yard. It is autumn, and the leaves are so bright yellow against the white bark, against the blue sky, that you get that sharp surge of joy and sadness you always get when you see something beautiful, especially in the fall when the natural world tells us that death — like birth, like hope, like love — is an inevitable, glorious, soaring thing. "That," you say to your baby, "is what beauty feels like. You'll see when you get out.

"You'll love it here," you say, and your heart fills the way it once did when you saw your husband across the room and you knew he was the man you would marry.

Thought everyone would enjoy that.. :)